KATHMANDU: The World Bank has delayed its loan agreement with Nepal for the 1,063 MW Upper Arun Hydropower Project following a request from the Indian government. In a recent letter to India, the World Bank confirmed that no loan agreement has been finalized, and the project is still under review. India had earlier urged the World Bank to reconsider its involvement in the project due to ongoing Indian-led hydropower projects downstream.

India’s request, sent in June, expressed concerns that the Upper Arun project could interfere with other Indian-led hydropower projects in the same river basin. In response, the World Bank informed India that discussions with Nepal are still ongoing, and a final decision would be made after further consultations.

The loan agreement, which was initially expected to be signed between the World Bank and Nepal in April 2024, has been repeatedly delayed. According to Nepal’s Ministry of Energy, the World Bank’s decision to delay the loan has been influenced by India’s concerns. This has further complicated the financing for the Upper Arun project, which is considered one of Nepal Electricity Authority’s (NEA) most significant initiatives.

India’s intervention comes at a critical time as Nepal had been preparing for the final construction phase of the project. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) were set to provide concessional loans to finance the project. However, India has requested that the responsibility for developing the Upper Arun project be handed over to Indian companies.

India’s strategic interest in the Arun River basin, where it has ongoing projects, is a key factor in its push to control the Upper Arun project. Indian company Satluj, which has already constructed transmission lines and road infrastructure in the region, has shown strong interest in taking over the project. If approved, Satluj would control the production of over 3,150 MW of electricity in the Arun Corridor.

The Indian proposal mirrors the model of the 900 MW Arun III project, where Nepal receives 21.9% of the electricity generated, free of charge. Similarly, under Indian control, the Upper Arun would provide Nepal with 224 MW of free electricity. Additionally, India plans to construct a 210-km long transmission line to export electricity to its national grid.

Despite the delays, Indian officials have been in direct communication with World Bank President Ajay Banga, himself of Indian origin, to influence the outcome. Sources within Nepal’s Ministry of Energy confirm that discussions between India and the World Bank have delayed the loan agreement and cast doubt on the future of the project under Nepali control.

Nepali officials are now under pressure to decide whether to accept India’s proposal or continue negotiations with the World Bank. With India’s commitment to importing 10,000 MW of electricity from Nepal over the next decade and the recently signed tripartite agreement to export power to Bangladesh via India, the outcome of this project could significantly impact Nepal’s energy sector and its broader economic ties with its southern neighbor.

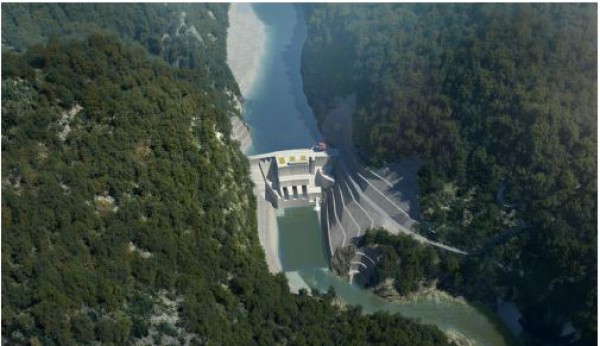

The Upper Arun project, estimated to cost USD 2.24 billion, remains one of Nepal’s most ambitious hydropower projects. However, the growing influence of India in the project’s development has raised concerns among Nepali officials and energy experts, who fear that handing over control to Indian companies may limit Nepal’s long-term benefits.

For now, the future of the Upper Arun project remains uncertain, as Nepal waits for a final decision from the World Bank and continues to weigh its options in the face of India’s increasing interest.